User:Michiexile/MATH198/Lecture 4

IMPORTANT NOTE: THESE NOTES ARE STILL UNDER DEVELOPMENT. PLEASE WAIT UNTIL AFTER THE LECTURE WITH HANDING ANYTHING IN, OR TREATING THE NOTES AS READY TO READ.

Product

Recall the construction of a cartesian product of two sets: . We have functions and extracting the two sets from the product, and we can take any two functions and and take them together to form a function .

Similarly, we can form the type of pairs of Haskell types: Pair s t = (s,t). For the pair type, we have canonical functions fst :: (s,t) -> s and snd :: (s,t) -> t extracting the components. And given two functions f :: s -> s' and g :: t -> t', there is a function f *** g :: (s,t) -> (s',t').

An element of the pair is completely determined by the two elements included in it. Hence, if we have a pair of generalized elements and , we can find a unique generalized element such that the projection arrows on this gives us the original elements back.

This argument indicates to us a possible definition that avoids talking about elements in sets in the first place, and we are lead to the

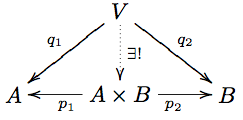

Definition A product of two objects in a category is an object equipped with arrows such that for any other object with arrows , there is a unique arrow such that the diagram

commutes. The diagram is called a product cone if it is a diagram of a product with the projection arrows from its definition.

In the category of sets, the unique map is given by . In the Haskell category, it is given by the combinator (&&&) :: (a -> b) -> (a -> c) -> a -> (b,c).

We tend to talk about the product. The justification for this lies in the first interesting

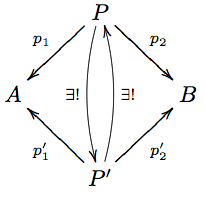

Proposition If and are both products for , then they are isomorphic.

Proof Consider the diagram

Both vertical arrows are given by the product property of the two product cones involved. Their compositions are endo-arrows of , such that in each case, we get a diagram like

with (or ), and . There is, by the product property, only one endoarrow that can make the diagram work - but both the composition of the two arrows, and the identity arrow itself, make the diagram commute. Therefore, the composition has to be the identity. QED.

We can expand the binary product to higher order products easily - instead of pairs of arrows, we have families of arrows, and all the diagrams carry over to the larger case.

Binary functions

Functions into a product help define the product in the first place, and function as elements of the product. Functions from a product, on the other hand, allow us to put a formalism around the idea of functions of several variables.

So a function of two variables, of types A and B is a function f :: (A,B) -> C. The Haskell idiom for the same thing, A -> B -> C as a function taking one argument and returning a function of a single variable; as well as the curry/uncurry procedure is tightly connected to this viewpoint, and will reemerge when we talk about adjunctions in a few lectures' time.

Coproduct

The product came, in part, out of considering the pair construction. One alternative way to write the Pair a b type is:

data Pair a b = Pair a b

and the resulting type is isomorphic, in Hask, to the product type we discussed above.

This is one of two basic things we can do in a data type declaration, and corresponds to the record types in Computer Science jargon.

The other thing we can do is to form a union type, by something like

data Union a b = Left a | Right b

which takes on either a value of type a or of type b, depending on what constructor we use.

This type guarantees the existence of two functions

Left :: a -> Union a b

Right :: b -> Union a b

Similarly, in the category of sets we have the disjoint union , which also comes with functions .

We can use all this to mimic the product definition. The directions of the inclusions indicate that we may well want the dualization of the definition. Thus we define:

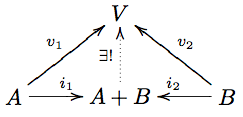

Definition A coproduct of objects in a category is an object equipped with arrows such that for any other object with arrows , there is a unique arrow such that the diagram

commutes. The diagram is called a coproduct cocone, and the arrows are inclusion arrows.

The other thing you can do in a Haskell data type declaration looks like this:

Coproduct a b = A a | B b

and the corresponding library type is Either a b = Left a | Right b.

This type provides us with functions

A :: a -> Coproduct a b

B :: b -> Coproduct a b

and hence looks quite like a dual to the product construction, in that the guaranteed functions the type brings are in the reverse directions from the arrows that the product projection arrows.

So, maybe what we want to do is to simply dualize the entire definition?

Definition Let be a category. The coproduct of two objects is an object equipped with maps and such that any other object with maps has a unique map such that and .

In the Haskell case, the maps are the type constructors . And indeed, this Coproduct, the union type construction, is the type which guarantees inclusion of source types, but with minimal additional assumptions on the type.

In the category of sets, the coproduct construction is one where we can embed both sets into the coproduct, faithfully, and the result has no additional structure beyond that. Thus, the coproduct in set, is the disjoint union of the included sets: both sets are included without identifications made, and no extra elements are introduced.

Proposition If are both coproducts for some , then they are isomorphic.

The proof is almost exactly the same as the proof for the product case.

- Diagram definition

- Disjoint union in Set

- Coproduct of categories construction

- Union types

Algebra of datatypes

Recall from [User:Michiexile/MATH198/Lecture_3|Lecture 3] that we can consider endofunctors as container datatypes. Some of the more obvious such container datatypes include:

data 1 a = Empty

data T a = T a

These being the data type that has only one single element and the data type that has exactly one value contained.

Using these, we can generate a whole slew of further datatypes. First off, we can generate a data type with any finite number of elements by ( times). Remember that the coproduct construction for data types allows us to know which summand of the coproduct a given part is in, so the single elements in all the 1s in the definition of n here are all distinguishable, thus giving the final type the required number of elements.

Of note among these is the data type Bool = 2 - the Boolean data type, characterized by having exactly two elements.

Furthermore, we can note that , with the isomorphism given by the maps

f (Empty, T x) = T x

g (T x) = (Empty, T x)

Thus we have the capacity to add and multiply types with each other. We can verify, for any types

We can thus make sense of types like (either a triple of single values, or one out of two tagged pairs of single values).

This allows us to start working out a calculus of data types with versatile expression power. We can produce recursive data type definitions by using equations to define data types, that then allow a direct translation back into Haskell data type definitions, such as:

The real power of this way of rewriting types comes in the recognition that we can use algebraic methods to reason about our data types. For instance:

List = 1 + T * List

= 1 + T * (1 + T * List)

= 1 + T * 1 + T * T* List

= 1 + T + T * T * List

so a list is either empty, contains one element, or contains at least two elements. Using, though, ideas from the theory of power series, or from continued fractions, we can start analyzing the data types using steps on the way that seem completely bizarre, but arriving at important property. Again, an easy example for illustration:

List = 1 + T * List -- and thus

List - T * List = 1 -- even though (-) doesn't make sense for data types

(1 - T) * List = 1 -- still ignoring that (-)...

List = 1 / (1 - T) -- even though (/) doesn't make sense for data types

= 1 + T + T*T + T*T*T + ... -- by the geometric series identity

and hence, we can conclude - using formally algebraic steps in between - that a list by the given definition consists of either an empty list, a single value, a pair of values, three values, et.c.

At this point, I'd recommend anyone interested in more perspectives on this approach to data types, and thinks one may do with them, to read the following references:

Blog posts

Research papers

d for data types 7 trees into 1

Homework

- What are the products in the category of a poset ? What are the coproducts?

- Prove that any two coproducts are isomorphic.

- Write down the type declaration for at least two of the example data types from the section of the algebra of datatypes, and write a

Functorimplementation for each.