Difference between revisions of "Xmonad/Guided tour of the xmonad source"

(add some initial content) |

DonStewart (talk | contribs) |

||

| (14 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{xmonad}} |

||

| + | [[Category:XMonad]] |

||

| + | |||

== Introduction == |

== Introduction == |

||

| Line 13: | Line 16: | ||

This is not a Haskell tutorial. I assume that you already know some |

This is not a Haskell tutorial. I assume that you already know some |

||

| − | basic Haskell: defining functions and data |

+ | basic Haskell: defining functions and data; the type system; standard |

| − | functions, types, and type classes from the Standard Prelude |

+ | functions, types, and type classes from the Standard Prelude; and at least |

a basic familiarity with monads. With that said, however, I do take |

a basic familiarity with monads. With that said, however, I do take |

||

frequent detours to highlight and explain more advanced topics and |

frequent detours to highlight and explain more advanced topics and |

||

| Line 21: | Line 24: | ||

==First things first== |

==First things first== |

||

| − | You'll want to have your own version of the xmonad source code as you |

+ | You'll want to have your own version of the xmonad source code to refer to as you read through the guided tour. In particular, you'll want the latest |

| − | read through the guided tour. In particular, you'll want the latest |

||

[http://darcs.net/ darcs] version, which you can easily download by issuing the command: |

[http://darcs.net/ darcs] version, which you can easily download by issuing the command: |

||

darcs get http://code.haskell.org/xmonad |

darcs get http://code.haskell.org/xmonad |

||

| + | I intend for this guided tour to keep abreast of the latest darcs changes; if you see something which is out of sync, report it on the xmonad mailing list, or -- even better -- fix it! |

||

| − | Without further ado, let's begin! |

||

| + | You may also want to refer to the [http://www.haskell.org/haddock/ Haddock]-generated documentation (it's all in the source code, of course, but may be nicer to read this way). You can build the documentation by going into the root of the xmonad source directory, and issuing the command: |

||

| − | == StackSet.hs == |

||

| + | runhaskell Setup haddock |

||

| − | StackSet.hs is the pure, functional heart of xmonad. Far removed from |

||

| − | corrupting pollutants such as the IO monad and the X server, it is |

||

| − | a beatiful, limpid pool of pure code which defines most of the basic |

||

| − | data structures used to store the state of xmonad. It is heavily |

||

| − | validated by [http://www.cs.chalmers.se/~rjmh/QuickCheck/ QuickCheck] tests; the combination of good use of types |

||

| − | (which we will see later) and QuickCheck validation means that we can be |

||

| − | very confident of the correctness of code in StackSet.hs. |

||

| + | which will generate HTML documentation in dist/doc/html/xmonad/. |

||

| − | ===<hask>StackSet</hask>=== |

||

| + | Without further ado, let's begin! |

||

| − | The <hask>StackSet</hask> data type is the mother-type which stores (almost) all |

||

| − | of xmonad's state. Let's take a look at the definition of the |

||

| − | <hask>StackSet</hask> data type itself: |

||

| − | <haskell> |

||

| − | data StackSet i l a sid sd = |

||

| − | StackSet { current :: !(Screen i l a sid sd) -- ^ currently focused workspace |

||

| − | , visible :: [Screen i l a sid sd] -- ^ non-focused workspaces, visible in xinerama |

||

| − | , hidden :: [Workspace i l a] -- ^ workspaces not visible anywhere |

||

| − | , floating :: M.Map a RationalRect -- ^ floating windows |

||

| − | } deriving (Show, Read, Eq) |

||

| − | </haskell> |

||

| − | First of all, what's up with <hask>i l a sid sd</hask>? These are ''type parameters'' to <hask>StackSet</hask>---five types which must be provided to form |

||

| − | a concrete instance of <hask>StackSet</hask>. It's not obvious just from this |

||

| − | definition what they represent, so let's talk about them first, so we |

||

| − | have a better idea of what's going on when they keep coming up later. |

||

| + | == StackSet.hs == |

||

| − | * The first type parameter, here represented by <hask>i</hask>, is the type of ''workspace tags''. Each workspace has a tag which uniquely identifies it (and which is shown in your status bar if you use the DynamicLog extension). At the moment, these tags are simply <hask>String</hask>s---but, as you can see, the definition of <hask>StackSet</hask> doesn't depend on knowing exactly what they are. If, in the future, the xmonad developers decided that <hask>Complex Double</hask>s would make better workspace tags, no changes would be required to any of the code in StackSet.hs! |

||

| − | |||

| − | * The second type parameter <hask>l</hask> is somewhat mysterious---there isn't much code in StackSet.hs that does much of anything with it. For now, it's enough to know that the type <hask>l</hask> has something to do with layouts; <hask>StackSet</hask> is completely independent of particular window layouts, so there's not much to see here. |

||

| − | |||

| − | * The third type parameter, <hask>a</hask>, is the type of a single window. |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <hask>sid</hask> is a screen id, which identifies a physical screen; as we'll see later, it is (essentially) <hask>Int</hask>. |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <hask>sd</hask>, the last type parameter to <hask>StackSet</hask>, represents details about a physical screen. |

||

| − | |||

| − | Although it's helpful to know what these types represent, it's |

||

| − | important to understand that as far as <hask>StackSet</hask> is concerned, the |

||

| − | particular types don't matter. A <hask>StackSet</hask> simply organizes data |

||

| − | with these types in particular ways, so it has no need to know the |

||

| − | actual types. |

||

| − | |||

| − | The <hask>StackSet</hask> data type has four members: <hask>current</hask> stores the |

||

| − | currently focused workspace; <hask>visible</hask> stores a list of those |

||

| − | workspaces which are not focused but are still visible on other |

||

| − | physical screens; <hask>hidden</hask> stores those workspaces which are, well, |

||

| − | hidden; and <hask>floating</hask> stores any windows which are in the floating |

||

| − | layer. |

||

| − | |||

| − | A few comments are in order: |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <hask>visible</hask> is only needed to support multiple physical screens with Xinerama; in a non-Xinerama setup, <hask>visible</hask> will always be the empty list. |

||

| − | |||

| − | * Notice that <hask>current</hask> and <hask>visible</hask> store <hask>Screen</hask>s, whereas <hask>hidden</hask> stores <hask>Workspace</hask>s. This might seem confusing until you realize that a <hask>Screen</hask> is really just a glorified <hask>Workspace</hask>, with a little extra information to keep track of which physical screen it is currently being displayed on: |

||

| − | |||

| − | <haskell> |

||

| − | data Screen i l a sid sd = Screen { workspace :: !(Workspace i l a) |

||

| − | , screen :: !sid |

||

| − | , screenDetail :: !sd } |

||

| − | deriving (Show, Read, Eq) |

||

| − | </haskell> |

||

| − | |||

| − | * A note about those exclamation points, as in <hask>workspace :: !(Workspace i l a)</hask>: they are ''strictness annotations'' which specify that the fields in question should never contain thunks (unevaluated expressions). This helps ensure that we don't get huge memory blowups with fields whose values aren't needed for a while and lazily accumulate large unevaluated expressions. Such fields could also potentially cause sudden slowdowns, freezing, etc. when their values are finally needed, so the strictness annotations also help ensure that xmonad runs smoothly by spreading out the work. |

||

| − | |||

| − | * The <hask>floating</hask> field stores a <hask>Map</hask> from windows (type <hask>a</hask>,remember?) to <hask>RationalRect</hask>s, which simply store x position, y position, width, and height. Note that floating windows are still stored in a <hask>Workspace</hask> in addition to being a key of <hask>floating</hask>, which means that floating/sinking a window is a simple matter of inserting/deleting it from <hask>floating</hask>, without having to mess with any <hask>Workspace</hask> data. |

||

| − | |||

| − | ===<hask>StackSet</hask> functions=== |

||

| + | StackSet.hs is the pure, functional heart of xmonad. Far removed from corrupting pollutants such as the IO monad and the X server, it is a beautiful, limpid pool of pure code which defines most of the basic data structures used to store the state of xmonad. It is heavily validated by [http://www.cs.chalmers.se/~rjmh/QuickCheck/ QuickCheck] tests; the combination of good use of types and QuickCheck validation means that we can be very confident of the correctness of the code in StackSet.hs. |

||

| − | StackSet.hs also provides a few functions for dealing directly with |

||

| − | <hask>StackSet</hask> values: <hask>new</hask>, <hask>view</hask>, and <hask>greedyView</hask>. For example, |

||

| − | here's <hask>new</hask>: |

||

| + | [[/StackSet.hs|Continue reading about StackSet.hs...]] |

||

| − | <haskell> |

||

| − | new :: (Integral s) => l -> [i] -> [sd] -> StackSet i l a s sd |

||

| − | new l wids m | not (null wids) && length m <= length wids = StackSet cur visi unseen M.empty |

||

| − | where (seen,unseen) = L.splitAt (length m) $ map (\i -> Workspace i l Nothing) wids |

||

| − | (cur:visi) = [ Screen i s sd | (i, s, sd) <- zip3 seen [0..] m ] |

||

| − | -- now zip up visibles with their screen id |

||

| − | new _ _ _ = abort "non-positive argument to StackSet.new" |

||

| − | </haskell> |

||

| + | == Core.hs == |

||

| − | If you're <hask>new</hask> (haha) to Haskell, this might seem dauntingly complex, |

||

| − | but it isn't actually all that bad. In general, if you just take |

||

| − | things slowly and break them down piece by piece, you'll probably be |

||

| − | surprised how much you understand after all. |

||

| + | The next source file to examine is Core.hs. It defines several core data types and some of the core functionality of xmonad. If StackSet.hs is the heart of xmonad, Core.hs is its guts. |

||

| − | <hask>new</hask> takes a layout thingy (<hask>l</hask>), a list of workspace tags (<hask>[i]</hask>), |

||

| − | and a list of screen descriptors (<hask>[sd]</hask>), and produces a new |

||

| − | <hask>StackSet</hask>. First, there's a guard, which requires <hask>wids</hask> to be |

||

| − | nonempty (there must be at least one workspace), and <hask>length m</hask> to be |

||

| − | at most <hask>length wids</hask> (there can't be more screens than workspaces). |

||

| − | If those conditions are met, it constructs a <hask>StackSet</hask> by creating a |

||

| − | list of empty <hask>Workspace</hask>s, splitting them into <hask>seen</hask> and <hask>unseen</hask> |

||

| − | workspaces (depending on the number of physical screens), combining |

||

| − | the <hask>seen</hask> workspaces with screen information, and finally picking the |

||

| − | first screen to be current. If the conditions on the guard are not |

||

| − | met, it aborts with an error. Since this function will only ever be |

||

| − | called internally, the call to <hask>abort</hask> isn't a problem: it's there |

||

| − | just so we can test to make sure it's never called! If this were a |

||

| − | function which might be called by users from their xmonad.hs configuration file, |

||

| − | aborting would be a huge no-no: by design, xmonad should never crash |

||

| − | for ''any'' reason (even user stupidity!). |

||

| + | [[/Core.hs|Continue reading about Core.hs...]] |

||

| − | Now take a look at <hask>view</hask> and <hask>greedyView</hask>. <hask>view</hask> takes a workspace |

||

| − | tag and a <hask>StackSet</hask>, and returns a new <hask>StackSet</hask> in which the given |

||

| − | workspace has been made current. <hask>greedyView</hask> only differs in the way |

||

| − | it treats Xinerama screens: <hask>greedyView</hask> will always swap the |

||

| − | requested workspace so it is now on the current screen even if it was |

||

| − | already visible, whereas calling <hask>view</hask> on a visible workspace will |

||

| − | just switch the focus to whatever screen it happens to be on. For |

||

| − | single-head setups, of course, there isn't any difference in behavior |

||

| − | between <hask>view</hask> and <hask>greedyView</hask>. |

||

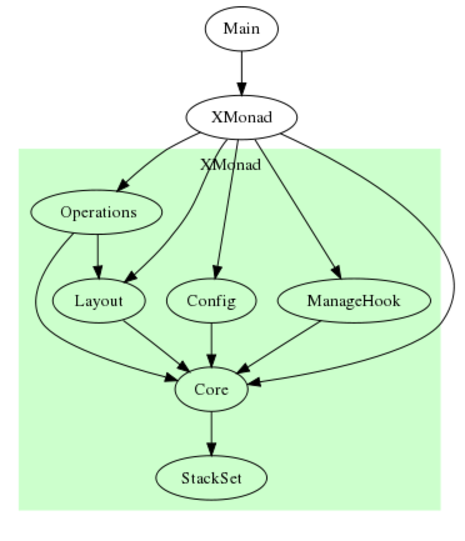

| + | == Module structure of the core == |

||

| − | Note that <hask>view</hask>/<hask>greedyView</hask> do not ''modify'' a <hask>StackSet</hask>, but simply |

||

| − | return a new one computed from the old one. This is a common purely |

||

| − | functional paradigm: functions which would modify a data structure in |

||

| − | an imperative/non-pure paradigm are recast as functions which take an |

||

| − | old version of a data structure as input and produce a new version. |

||

| − | This might seem horribly inefficient to someone used to a non-pure |

||

| − | paradigm, but it actually isn't, for (at least) two reasons. First, a |

||

| − | lot of work has gone into memory allocation and garbage collection, so |

||

| − | that in a modern functional language such as Haskell, these processes |

||

| − | are quite efficient. Second, and more importantly, the fact that |

||

| − | Haskell is pure (modifying values is not allowed) means that when a |

||

| − | new structure is constructed out of an old one with only a small |

||

| − | change, usually the new structure can actually share most of the old |

||

| − | one, with new memory being allocated only for the part that changed. |

||

| − | In an impure language, this kind of sharing would be a big no-no, |

||

| − | since modifying the old value later would suddenly cause the new value |

||

| − | to change as well. |

||

| + | [[Image:Xmonad2.svg|The module structure of the xmonad core]] |

||

| − | ===Other types=== |

||

Revision as of 16:30, 16 September 2008

Introduction

Do you know a little Haskell and want to see how it can profitably be applied in a real-world situation? Would you like to quickly get up to speed on the xmonad source code so you can contribute modules and patches? Do you aspire to be as cool of a hacker as the xmonad authors? If so, this might be for you. Specifically, this document aims to:

- Provide a readable overview of the xmonad source code for Haskell non-experts interested in contributing extensions or modifications to xmonad, or who are just curious.

- Highlight some of the uniquenesses of xmonad and the things that make functional languages in general, and Haskell in particular, so ideally suited to this domain.

This is not a Haskell tutorial. I assume that you already know some basic Haskell: defining functions and data; the type system; standard functions, types, and type classes from the Standard Prelude; and at least a basic familiarity with monads. With that said, however, I do take frequent detours to highlight and explain more advanced topics and features of Haskell as they arise.

First things first

You'll want to have your own version of the xmonad source code to refer to as you read through the guided tour. In particular, you'll want the latest darcs version, which you can easily download by issuing the command:

darcs get http://code.haskell.org/xmonad

I intend for this guided tour to keep abreast of the latest darcs changes; if you see something which is out of sync, report it on the xmonad mailing list, or -- even better -- fix it!

You may also want to refer to the Haddock-generated documentation (it's all in the source code, of course, but may be nicer to read this way). You can build the documentation by going into the root of the xmonad source directory, and issuing the command:

runhaskell Setup haddock

which will generate HTML documentation in dist/doc/html/xmonad/.

Without further ado, let's begin!

StackSet.hs

StackSet.hs is the pure, functional heart of xmonad. Far removed from corrupting pollutants such as the IO monad and the X server, it is a beautiful, limpid pool of pure code which defines most of the basic data structures used to store the state of xmonad. It is heavily validated by QuickCheck tests; the combination of good use of types and QuickCheck validation means that we can be very confident of the correctness of the code in StackSet.hs.

Continue reading about StackSet.hs...

Core.hs

The next source file to examine is Core.hs. It defines several core data types and some of the core functionality of xmonad. If StackSet.hs is the heart of xmonad, Core.hs is its guts.

Continue reading about Core.hs...